Originals

Douglas Grosse

A portrait of two significant Jewish doctors: Erich Langer and Ludwig Levy-Lenz

Keywords | Summary | Correspondence | References

Keywords

cosmetic medicine, cosmetic surgery, Dermatology, Erich Langer, Ludwig Levy-Lenz, national socialism, rejuvenation surgery, sexology

Schlüsselworte

Summary

Erich Langer and Ludwig Levy-Lenz were two outstanding personalities of their time. Levy-Lenz was active in various interrelated medical fields of venereology, gynaecology, surgery, cosmetic medicine and sexology. He wrote a number of popular writings, including the booklet How to protect yourself against venereal diseases in 1919. His rejuvenation operations and sex changes of both sexes already in the 1920s made him world famous. In 1952 he was the founder of this magazine. Erich Langer is one of those doctors who have made a great contribution to dermatology, but who are hardly known to younger dermatologists today. His energetic work and his writings after World War II paved the way for German dermatology to be recognized abroad again relatively quickly. Both were friends of my grandfather and played a major role in our publishing house. On the occasion of our anniversary, I would like to use this article to introduce both personalities, not only to our regular readers.

Zusammenfassung

Introduction

Erich Langer and Ludwig Levy-Lenz were outstanding physicians who never turned their backs on Germany, despite National Socialism and its terror. Their contribution to the reconstruction of German dermatology and aesthetic surgery is invaluable.

In 1933, about 16% of the medical profession in Germany was Jewish – with a population share of only 0.8%. In Berlin alone, more than half of all physicians were Jewish. A quarter of all dermatologists in the German Reich were Jewish. Already at the beginning of the 20th century, the predominance of Jewish doctors in dermatology was a tradition. Young doctors often followed in the footsteps of their fathers or relatives. The history of dermatology is full of Jewish fathers and sons, such as Joseph and Werner Jadasohn, Samuel and Max Jessner, as well as Felix and Hermann Pinkus.

Within a short time after Hitler’s seizure of power, most leading dermatologists were fired and forced to emigrate. Of the 2078 dermatologists in 1933, 566 were Jewish. 248 emigrated, mostly to the USA. 58 died in Germany, of which at least 10 committed suicide. At least 60 dermatologists died in the concentration camps.

Erich Langer

Erich Langer was one of the few Jews who had remained in Berlin. In contrast to the greats of dermatology such as Abraham Buschke (1868 – 1943) and Karl Herxheimer (1861 – 1942) who died in concentration camps or who took their own lives, such as Fritz Juliusberg (1872 – 1939; pityraisis lichenoides chronica) and Ernst Kromayer (1862 – 1933; Kromayer Lampe), little is known about the Jews who remained in Berlin [1].

In 1927, Langer became the conducting physician of the new Clinic for Dermatology and director of the Clinic for Venerology in Berlin-Britz, a large clinic in Neukölln, then a poor district of Berlin. With his wife Margarete, he moved into a large apartment at Knesebeckstraße 67, near the elegant Kurfürstendamm, where he also opened a private practice, attracting a wealthy clientele. He became a respected member of the Berlin and German dermatology scene. The situation also looked promising for other Jewish dermatologists. Some were even promoted to professorship, which a generation before would have been almost impossible [1].

In April 1933 he was forced to take leave from Berlin-Britz (Neukölln) and was dismissed in October of the same year. Originally, he also lost his health insurance licence, but here his military career and the Iron Cross he was awarded during World War I helped him. He got his health insurance licence back and treated public and private patients in his home practice until well into 1938 [1].

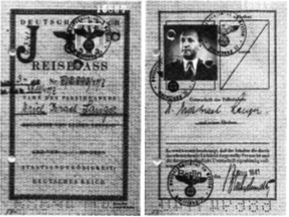

Fig. 2: Erich Langer‘s passport from 1941 with the stamp „J“ and the middle name „Israel“. (With the permission of the Berlin State Office for Citizens and Public Order).

The situation for the Jews became increasingly difficult. Actually, Erich Langer was planning to leave Germany. But his greatest concern was his parents, who were no longer young, whom he had been supporting financially since 1930. After the Reichskristallnacht on November 9, 1938, he took his parents in. His brother and his sister-in-law went to Sao Paolo, Brazil in 1939 and returned in 1950. The attempt to emigrate to Sweden with his wife and parents failed. Later he decided to go to the USA. At the beginning of 1941 he was issued passports, opened the necessary bank account, bought tickets for the crossing in the amount of 10,000 Reichsmark and hired a moving company. But then his request was rejected by the German authorities [1].

Erich Langer remained in Berlin throughout the war. His greatest help, although little documented, was certainly his Christian wife Margarete. The Langers were able to stay in their Charlottenburg apartment until the house was bombed in November 1943. They later lived illegally in the suburb of Zehlendorf with the Heiligental family at Eggepfad 18, a street of terraced houses bordering houses built for members of the SS [1].

A unique trick to avoid prosecution was to declare yourself illegitimate. Langer went through this procedure in 1942, and his mother had to testify that she had an affair with Friedrich Klingsporn, an Aryan, and that she had not had sexual intercourse with her husband Theodor before Langer was born. She complained that Klingsporn was Langers biological father, and Langer therefore, only half Jewish. This was accepted by a Berlin court; the blood test results could not exclude that Theodor Langer was Erich’s father, but the medical examination by a specialist in hereditary biology determined that Erich had too many Aryan characteristics to be a full Jew. Ironically, some prominent Nazis undertook the same trick to make themselves Aryans; Erhard Milch (1892 – 1972), Field Marshal of the Luftwaffe, had a Jewish father, but his mother also testified that he was illegitimate. Shortly afterwards, Langer’s parents were deported to Theresienstadt near Prague, where they died [1].

Langer was able to evade the authorities until December 1944. Then his arrest was ordered after several illegal Jews whom he had treated were arrested and denounced him. The person collecting him was a former patient of his who let him escape. In Langer’s own words, “I managed to avoid all other attempts to pick me up.” Towards the end of 1944, Langer’s wife suffered from a bowel obstruction and needed surgery, most likely performed at the Jewish Hospital. After her release she was ordered to work in a leather factory, which she did until the end of the war. From then on, he went underground. According to his own statement, he spent 6 months in a garden shed on an island in the Tegeler See, one of many lakes in Berlin [1].

After the capitulation of the 3rd Reich on 8 May 1945, Langer returned to Berlin-Britz in July and again took over the leadership of the Dermatovenerology Department. A picture from this time shows the effects of his underground existence and starvation (Fig. ).

Fig. 3: Erich Langer 1945 after the end of the war (Foundation New Synagogue Berlin, Centrum Judaicum, Archive [CJA 4.1. No. 996]).

From May 1945 the Langers lived in an old villa at 321 Kornprinzenallee (renamed Clayallee in 1949 after the American General Lucius D. Clay, the mastermind of the Berlin Airlift). In 1952 they moved again to Charlottenburg at Mommsenstraße 7, where he also had a private practice.

In addition to his work as editor of the Zeitschrift für Haut- und Geschlechtskrankheiten, Langer also published other books in our publishing house, such as „Sexually transmitted Diseases in Children and Adolescents“ (together with Wilhelm Brandt) and the „Atlas of Syphilis, which became a classic for all practicing doctors.

Langer also helped to revive the German Society for the Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and the Berlin Dermatological Society.

His wife Margarete died in the summer of 1957. He followed her a few months later and died unexpectedly in an unsuitable environment. After attending a conference in Vienna in autumn, he made a stopover in Feldafing on Lake Starnberg to play in one of the first and most renowned golf clubs. On the golf course he suffered a heart attack. After a few weeks he died in a local clinic on 21 October 1957.

Ludwig L. Lenz

Ludwig Levy-Lenz was born on 1 December 1892 in Posen (now polnish Poznan) into a wealthy middle-class family. In 1909 he went to Heidelberg together with his younger brother Siegbert to study medicine. This was followed by stations in Munich and Breslau. At the beginning of the First World War he was stationed as a soldier in Posen in a special hospital he had set up himself for reconstructive surgery and orthopaedics. On behalf of his military superiors he even set up a war brothel and was responsible for the health care of the women working there.

Shortly after the war, he opened a medical practice in Berlin at Rosenthaler Platz, very close to the Jewish Scheunenviertel. Around 1926, after the divorce from his first wife Denise, he moved to the bourgeois Westend of Berlin. His second marriage to Elma Wilhelm lasted only until 1932 and at the beginning of 1933 he married Marya Goldwasser, twenty years his junior, in his third marriage. In the run-up to the Olympic Games he believed in a relaxation of German anti-Semitic politics and returned to Germany, only to finally emigrate to Egypt in 1937. There he was able to open a cosmetic surgery practice. In 1939 he was expatriated by the Greater German Reich.

Works by Levy-Lenz were also translated into other languages, and in France a translation was even printed during the German occupation in 1943. After the end of the war, Lenz worked, seasonally alternating between Baden-Baden and Cairo, and finally returned to Berlin in 1965.

Rejuvenation operations

The physiologist and sexologist Eugen Steinach (1861 – 1944) had been working since the 1890s on the analysis and use of sex hormones and on experiments on sex reassignment surgery, which he published from 1912 onwards and thus aroused worldwide public interest. Above all, he caused a sensation with his “rejuvenation operations” but also with his theses on the “treatment” of homosexuality after the First World War, which also brought him massive hostility.

In 1921 Levy-Lenz went to Vienna together with his colleague Peter Schmidt to learn about Eugen Steinach’s rejuvenation methods. Just one year later, the two of them began to carry out “rejuvenation operations” (vasoligatura – the interruption of the spermatic duct or testicular transplants) together in Berlin. The cultural department of Ufa (the largest German film company) filmed these operations. The material is used in the versions of “Steinachs Forschungen”(Steinachs Research) and “Der Steinach Film” (The Steinach Film), completed in 1922/23. Later, Ufa filmed Lenz during the first so-called Voronoff operation, during which – with the same aim – the testicles of a rhesus monkey were implanted into a man. Unlike Schmidt, Lenz later turned away from these operations.

Tab. 1: Overview of the most important publications by Ludwig Levy-Lenz.

| – Peter Schmidt & Ludwig Levy-Lenz. The success of Steinach treatment in humans, Berlin: G. Ziemsen, 1921. |

| – Magnus Hirschfeld & Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Sexual Disasters: Images from modern sex and married life. Leipzig: Payne, 1926. |

| – Maria Winter & Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Abortion or contraception of pregnancy? Berlin-Hessenwinkel: Publishing House of the New Society, 1928. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. The Enlightened Woman: a book for all women. Berlin: Man-Verl, 1928. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Janine: Tagebuch einer Verjüngten, Berlin: Man Verlag, 1928. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. When women aren’t allowed to give birth: “The meaning and method of contraception in general. Berlin-Hessenwinkel: Publishing House of the New Society, 1928. |

| – Arthur Koestler, A. Willy, Norman Haire & Ludwig Levy-Lenz. The Encyclopeadia of Sexual Knowledge. London: F. Aldor, 1934. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. La femme initiée, Paris: Le Caire, R. Schindler, 1943. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Discreet and Indiscreet: (Memoirs of a Sexologist). Dischingen/Wurttemberg: Wadi-Verlagsbuchhandlung, 317pp 1951. English translation as Discretion and indiscretion: memoirs of a sexologist. New York: Cadillac Pub. Co., 512 pp 1951. |

| – Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Practice of cosmetic surgery. Advances and dangers, 1954. |

Ludwig L.-Lenz and sexual science

Through the “soldiers’ brothel” he set up in World War I, he realized that there was not only a military front, but also a psychological and physical one, outside of obedience. To unfold freely and to surrender to his feelings and inclinations, to experience pleasure. There was not only the enemy at the front, but also the enemy of venereal diseases and, for the women who were forced into prostitution, the unwanted pregnancy. After the war he therefore wanted to pacify the remaining fronts of venereal diseases and unwanted pregnancy. As early as 1919 he published the brochure Wie schütze ich mich vor Geschlechtskrankheiten? (How do I protect myself against venereal diseases), which was distributed in public toilets and to certain establishments. The brothel he ran on the orders of his superiors led him to look into the social position of women and gender roles in general. The titles of his books speak for themselves: When women are not allowed to give birth: Meaning and Method of Contraception Presented in an Easily Understandable Way (1928), The Enlightened Woman (1928) and Love’s Cauldron (1931).

His approach to the study of gender roles was similar to that of Magnus Hirschfeld. From 1925 Lenz worked at Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexology. There he was head of the women’s department and was actively involved in the women’s advice centre. He outlined his tasks at the institute as follows: “I was head of the women’s department and the counseling center, but also had to temporarily work on court reports and hold question evenings”. His actual activity, however, was surgery with a focus on genital operations. He carried out castrations of sex offenders, vasoligature and testicle transplantation for those who wanted to rejuvenate.

In June 1931 Lenz performed a penectomy on a well-known transvestite named Dorchen Richter. The surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt (1890-1965) created an artificial vagina. It was the first known sex change worldwide, just a few months before the sex-alignment operation performed on the artist Lili Elbe.

In the period following National Socialism, the proportion of contributions on sexual science declined. In this respect, he fails to reconnect to the sex sciences. In Germany, sexology was newly formed within psychiatry – a direction that was far from his own. In addition, he was very close to Magnus Hirschfeld, which he never concealed, unlike other members of the institute. Hirschfeld’s orientation in sexual science, and above all in sexual politics, was highly suspect to a number of psychiatrically oriented sexologists, not only because of Nazi propaganda [3].

Levy-Lenz is able to pick up the thread again. In 1951 he published his memoirs, begun ten years earlier in Cairo, under the significant title Discreet and Indiscreet. In 1952, he reissued an updated version of The Enlightened Woman (1st edition) and “Janine, Diary of a Younger” also had a post-war edition. In 1952 the journal „Journal Ästhetische Medizin und Sexologie“ – today’s Cosmetic Medicine – was founded.

The last highly regarded scientific work is the first post-war guide to cosmetic surgery (1954). An obituary shows that Ludwig-Lenz was a gifted teacher in the field of cosmetic surgery who succeeded in building up a circle of students [4].

Address of Correspondence

Douglas Grosse

GMC Gesundheitsmedien und Congress GmbH

Mommsenstr. 30

DE-10629 Berlin

grosse@gmc-medien.de

Conflict of Interests

No financial interests. Douglas Grosse is publisher of the journal Cosmetic Medicine

References

1. Burgdorf WHC, Hoenig LJ, Plewig G, Kohl PK (2014) Erich Langer: The last Jewish dermatologist in Nazi Berlin. Clin Dermatol 32: 532 – 541.

2. Albrecht Scholz, Karl Holubar, Günter Burg (Hg.): Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Dermatologie, Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft 2009, S. 103.

3. Sigusch V, Grau G (2009) Personenlexikon der Sexualwissenschaften. Campus Verlag S.: 421 – 423.

4. Harnisch H et al (1966) Nachruf Ludwig Levy-Lenz. Ästh Med 15: 389.